The Bosses Are Back

Evangelical ethics are being challenged by the re-emergence of political machines.

Evangelicals are debating their relationship to political power now that Donald Trump has returned to the White House. Partisans are offering theological grounds for their justifications or condemnations, as if Trump has a philosophy or agenda that we are able to evaluate in a principled way. But something of the nature of power has changed over the last twelve years. That change is bigger than Trump. Power is no longer legitimized by effective persuasion, but by favors and punishments. Theologically, we haven’t come to grips with that change yet.

So let me tell you a story.

When John F. Kennedy arrived in Los Angeles to claim the Democratic nomination for president in 1960, he had accomplished seemingly impossible feats. He had leaped over the party’s many experienced pols—Adlai Stevenson, Lyndon Johnson, and Hubert Humphrey, to name just three. He had become the front runner as a Roman Catholic. And he had done so as a very young man running on a very thin resume. These feats are notorious.

His biggest feat of all is less well known and more important.

Many presidents after the Civil War entered the White House owing debts to city bosses around the country, the men who ran political machines. A boss knew his city ward by ward and controlled it using the officials he had placed at every level. He controlled cops or building inspectors. He also controlled department administrators, city councilmen, or city attorneys. At the highest levels, he might control mayors, judges, congressmen, governors, and senators. The boss’s control was exercised through relationships, favors, and punishments. A president was indebted to them because they delivered votes.

Think comic books. Everyone fears the boss. No one crosses the boss and gets away with it.

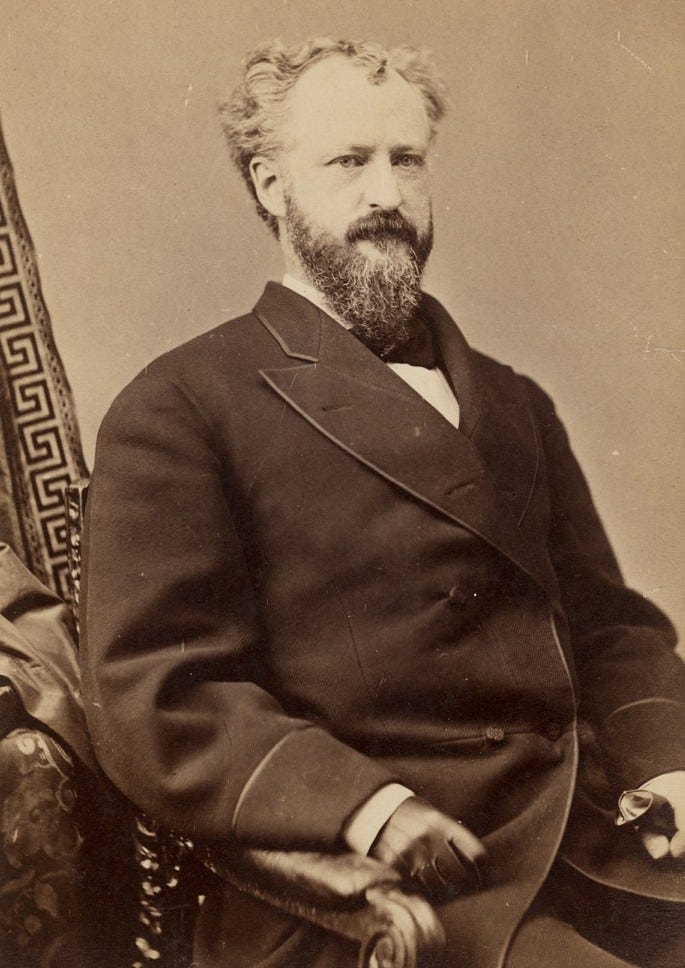

Some presidents were themselves machine politicians. Chester A. Arthur was a cog in Roscoe Conkling’s New York City machine. Placed in the vice presidency, Arthur succeeded the assassinated James Garfield in 1881.1 Harry Truman also succeeded a dead president in 1945, winning election in his own right in 1948. Truman’s career was launched by the Pendergast machine in Kansas City.

It wasn’t so long ago that elections were brazenly fixed by machines. For much of the 20th century in Texas, candidates’ election day totals were routinely held back until bosses knew how many votes they needed to acquire. Lyndon Johnson used this tactic in 1948, when he ran for the U.S. Senate, buying Mexican-American votes in Texas’s southern counties. But sometimes, as in Johnson’s case, the fix was too brazen and became scandalous.2

Kennedy’s biggest feat was that he did not have to court the city bosses to secure his nomination. They had to court him. He had subdued them before arriving in L.A.

Since 1956, Kennedy had built a county-by-county organization across the U.S. It was bound to him personally. He knew the local leaders. He understood local issues from their point of view. This network enabled him to win state primaries, which were previously unimportant in the nomination process. To wage this campaign, Kennedy tied his intricate local relationships to stunning mass media techniques. He used his and his wife’s magnetism, the star power of the Kennedy family, and the wattage of celebrity glitz he commanded to overwhelm television sets.

No previous candidate for president had done anything quite like this.

He outmaneuvered the men who had votes in their pockets. His success at the local and mass media levels meant that the bosses, who were accustomed to being the decisive power brokers at national conventions, were sidelined. Kennedy’s nomination was almost sewn up by delegate votes.

On the first ballot, when Wyoming put Kennedy over the top, the city bosses left the convention hall one by one and gathered at the Kennedy command center in a nearby cottage. They stood at a distance from the nominee. When they were summoned as a group, each boss waited deferentially until Kennedy greeted him. When Kennedy set out for the hall, the bosses formed a phalanx around him, carving a path for the victor through the converging crowds.3

To be sure, the bosses still had influence. Kennedy’s margin of victory that November was less than 100,000 votes nationally, coming mainly from Richard Daley’s Chicago and Johnson’s Texas. (A certain murkiness still hangs over that election.) Some vestiges of machine-style power remained part of Democratic conventions even in 2016. Hilary Clinton snatched the nomination from Bernie Sanders because “super delegates,” elected Democratic office holders, swung their support to her. After she lost the general election that fall, Democrats limited the role of super delegates in the nominating process.

But once the bosses lost control in 1960, the model for a winning presidential campaign imitated Kennedy’s: build an independent national organization to win primaries and the general election, and to make a mass media case to the voters.

The virtue of this model was that a new president could claim his own mandate to govern. He had, after all, made his argument to the voters directly. They showed that they had listened and agreed. His power as president was legitimate. But this model also had a problem. It took charisma, stamina, and luck to keep any mandate vigorous for four years—and most presidents failed to do so.

What we face now is the return of machine politics, with a twist.

In both parties, the bosses are back. No one crosses them and gets away with it. But they don’t operate the same way as when they ran cities or states. They are media or PAC bosses now, granting favors and meting out punishments through dollars, platforms, posts, or hashtags, not goons.

Most evangelicals seem not to have realized that Donald Trump is a boss. He is not bound by any platform, any principles, or any philosophy. He just has friends and enemies. This one consideration sharpens the ethical dilemma evangelicals face in their relationship to power. Can a godly person flatter, manipulate, placate, or cower before a boss? Can he or she be a goon when the boss demands proof of loyalty? How would he or she do those things and still maintain integrity?

Bluntly, how should evangelicals relate to the Trump machine?

Don’t miss any posts in this new series! Next post: How the new political machines work.

See Candice Millard’s Destiny of the Republic for the remarkable story of Garfield’s election and how Garfield drove Conkling from the U.S. Senate.

Biographer Robert Caro documented how Johnson stole the 1948 election, dispelling four decades of rumor in Means of Ascent.

See Chapter 6 of Theodore H. White’s The Making of the President 1960 for a masterful account of this convention.

Thanks for opening up a discussion about this. As always, you show us that history has a lot to teach us, and I'm really looking forward to how this series will unfold.